Manufacturing Machines: An Abridged History

What would you do if a manufacturing machine part broke? Chances are you’d get a replacement from your warehouse, order the part from a supplier or call someone to fix your machine. But that’s only because you live in the 21st century. Hundreds of years ago, your options — and your manufacturing equipment — were far more limited.

Manufacturing essentially began with six simple machines: lever, wheel and axle, inclined plane, wedge, pulley and screw. Granted, it may have taken several hundred years to go from the lever to the screw, but these six machines started to ease manual labor and increase human productivity. In fact, the machine you need to repair today arose from these early tools.

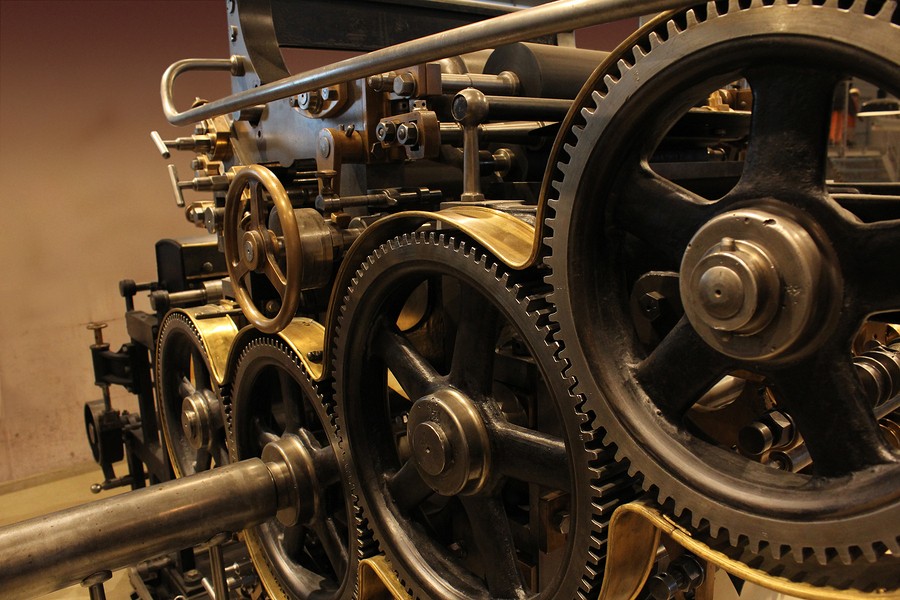

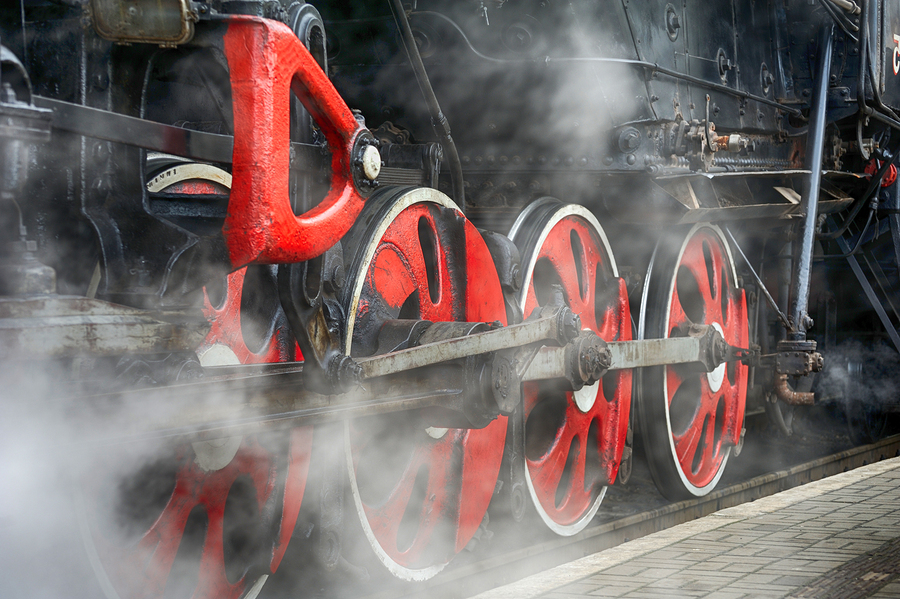

Today’s machinery stems from Industrial Revolution innovations generated at the beginning of the 18th century. Steam engines provided tremendous power and, unlike the horses preceding them, required no food or rest. The steam engine also transformed goods transportation when, in the early 1800s, Robert Fulton invented the first steamboat.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, craftspeople made most goods by hand on an as-needed basis and transported them by wagon if not used on-site. Afterward, factory workers produced items in bulk and transported them worldwide.

Some of the first industries affected were the textile, mining, glass, and agricultural sectors. The spinning wheel and loom propelled cotton over wool as the primary material in clothing manufacturing, shortening both actual production time and long-term growth cycles as farmers could plant and harvest cotton much more quickly than sheep could grow wool.

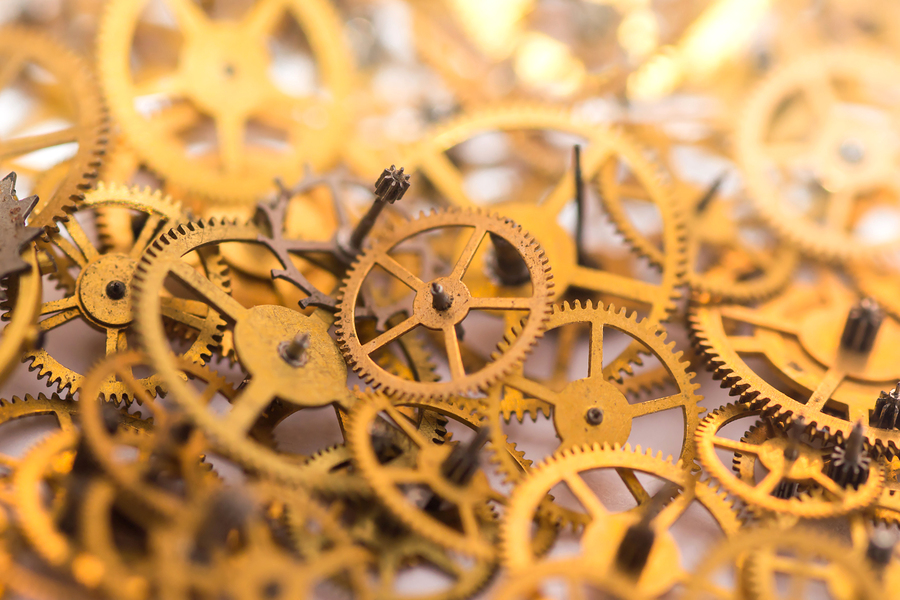

Another significant Industrial Revolution concept that increased machine productivity and decreased downtime was that of interchangeable parts. In the late 1700s, Honoré Blanc found he could replace broken pieces on his machinery more easily if he used uniform parts. Eli Whitney, famous for his cotton gin invention, adapted this idea for the American army muskets he built under a directive from former President George Washington.

From the simple lever you use to operate your equipment to the standardized parts you use for its repair, much of the impetus for machinery improvement involved decreased manual labor and increased productivity. Of course, as machines grew more complex, maintenance and repair also became increasingly more time-consuming and difficult.

However, you don’t have to face these manufacturing issues alone.